Principle SDC food system lenses

Some of the entry points through which SDC works with food systems.

K-HUB > SDC's Institutional Orientation > Principle SDC food system lenses

Nutrition

SDC’s main nutrition priorities:

- Enabling conducive framework conditions for healthy diets for all, particularly the most vulnerable groups (diet quality data; projects promoting regulatory capacities for ex. of food environment; projects strengthening human right-based legislation for food; strengthening coordination and multi-stakeholder and multisectorial dialogue);

- Strengthening nutrition-sensitive rural-urban value chains for a healthy and diverse local diet and improved livelihoods with inclusive and participatory markets and governance;

- Enhancing consumers’ demand and access for healthy and sustainably produced food choices through capacity building, information and behaviour change;

- Preventing and treating acute and chronic undernutrition among most vulnerable groups (in particular via partners’ interventions, using for example cash transfers);

- Encourage localisation of food production and consumption both for short term (emergency) interventions as well as long term development.

SDC’s main approaches:

- Applying a right-based approach to nutrition

- Preventing and fighting malnutrition in all its forms (undernutrition, overweight and obesity, and micronutrient deficiency) through promoting a healthy and diverse diet for all as it is the number one risk for health (i.e., non-communicable diseases)

- Addressing the malnutrition in a multi-sectoral way and from a food system perspective, and promoting nutrition-sensitive approaches in agriculture and production, or in social protection schemes

- Facilitating a multi-stakeholder approach, including civil society and private sector as they both play a central role in promoting and providing healthy diets

- Working towards enabling policy and regulatory environments.

Agroecology

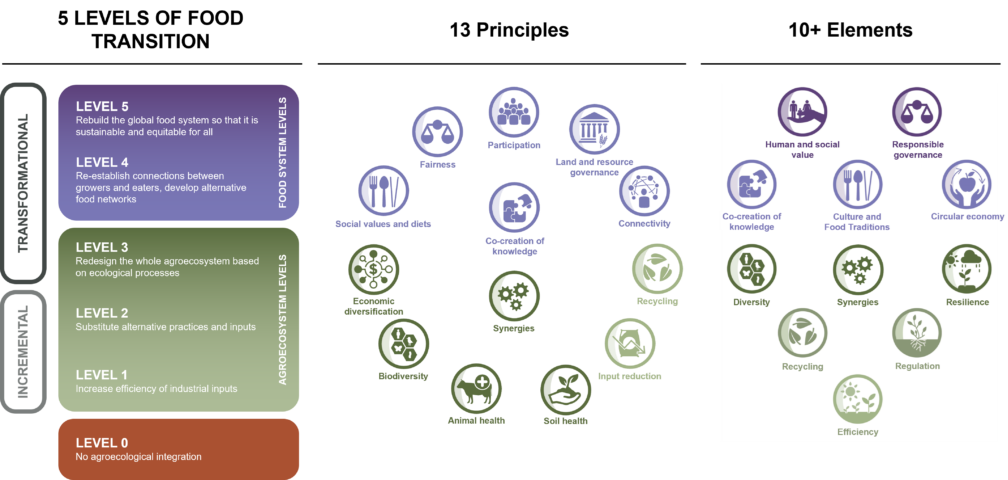

Agroecology as a concept has developed over the past few decades, moving away from a focus on fields and farms to include the entirety of agriculture and food systems. It has various definitions, which also differ by geographic location. Most commonly, the 5 levels of transition of Gliessman (2015), the 10 elements of the FAO (2018) and the 13 principles of Agroecology as defined by the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) from the CFS (2019) are used. The main difference between the two frameworks is that the 13 principles include explicit references to soil and animal health, and that they distinguish between biodiversity and economic diversification:

Agroecology has become a comprehensive and integrated framework and practice that factor in ecological and social principles and concepts when designing and managing sustainable food and agricultural systems. As such, agroecology is simultaneously a scientific discipline, a set of farming practices and a social movement, and extends far beyond farming practices. In addition to addressing the need for socially equitable food systems that give people choice over what they eat and how and where it is produced, agroecology aims to maximise interactions between plants, animals, humans and the environment. It has become a transdisciplinary field that covers all aspects of food systems from production to consumption, including their ecological, sociocultural, technological, economic and political dimensions, promoting environmentally-friendly practices and healthy nutrition, while embedding at its core the values of fairness, participation, localness, food sovereignty and social justice. It champions gender equality and community empowerment, elevates the role of farmers, and fosters local value chains, supporting dignified income and living conditions.

Key priorities:

- Switzerland, one of the front-runners, positions agroecology as a compass for food systems transformation towards more sustainability, resilience, health and equity, valuing its holistic and systemic approach.

- The cooperation among stakeholders from politics, science, the private sector, the finance sector, and civil society, as well as an inclusive rural community, are key elements supporting poverty reduction and improved livelihoods.

Some key challenges:

- Despite these global definitions, the use and understanding by the stakeholders vary in various parts of the globe, with usually a strong positioning from the civil society, closely linked to the human rights-based approaches.

- While there are no minimal standards nor predefined verification requirements, tools have been or are being developed to assess the fulfilment of the principles, such as at

- farm level (e.g. TAPE of FAO)

- the level of an enterprise (e.g. B-ACT of Biovision)

- project / portfolio level or during the development of a project (e.g. Agroecology finance assessment tool of the Agroecology Coalition)

- While globally the momentum placing agroecology as a paradigm shift to food system transformation is growing, the term agroecology is not very commonly used within markets, notably related to the challenge of traceability and monitoring, and overlaps with the organic sector.

Private-Sector Cooperation

Private business and entrepreneurship are the backbone of food systems almost everywhere. Accordingly, food system transformation towards healthier diets and a sustainable management of natural resources will not happen without the participation of private sector actors who must at the very least be able to function within the envisioned paradigm, but better still, themselves be willing to contribute to transformative outcomes. There are two aspects, first, private sector development, which seeks to grow and strengthen local entrepreneurship and should ideally entail agroecology and nutrition-sensitive value chains, then there is private sector engagement which more specifically focusses on businesses. Ideally, the two approaches should be combined.

Just to achieve SDG 2, there is currently an investment gap of USD 33-50 billion per annum which development finance alone cannot aspire to fill. Accordingly, investment pathways must be opened for individual farmers of all sizes, service providers for agriculture and value chains, research institutions and equipment producers which demonstrate that there is also a business case for investing in food system transformation at various scales.

Based on its focus areas related to food systems and health, SDC is working with the private sector, mainly through various approaches to so-called catalytic finance. This involves setting new incentives for businesses and farmers to make specific investments, e.g., agroecological production or nutrition-positive supply chain management. The objective is to first prove, then improve, the business case for such ventures, the result being that a dollar of development finance will invoke multiple dollars of investment in positive food system transformation while simultaneously adding to the livelihoods and income of those working in the food system sector. A particular focus is the so-called “missing middle”, which refers to value-chain actors, especially SMEs, seeking finance between USD 50,000 and USD 2 million and currently falling below the range of loan portfolios of commercial banking but also being above those of microfinance institutions.

The HDP nexus and Resilience

The recent increase of needs has led to a situation in which funding for humanitarian assistance has far outstripped funding for development. However, as of 2023, only 4% of global humanitarian assistance is spent on supporting agricultural livelihoods. A major challenge is to bring the food systems approach into humanitarian and fragile contexts. The underlying conceptual challenge is to introduce the holistic and longer-term endeavour of improving food systems in humanitarian contexts, taking into account the very immediate objectives of emergency assistance and the need to protect and transform the contextual structures fundamental to development. Particularly in protracted crisis situations, this means considering how the long-term structures for food security can be improved, often without having the legal and financial regulatory framework that stronger States have. One promising avenue of exploration is that of resilience. Here emergency assistance and longer-term planning can meet, and food systems thinking be applied. This also entails a mindset in how assistance is administered, and with it, the need to advance beyond scattered, siloed, short-term, and small-scale interventions:

- Convergence, not scattered activities à Integrated packages and concentrated interventions which are tailored to the context

- Scale, not small projects à Seek «high-impact interventions» to be complemented by partners

- Community owned, not externally motivated à government and community participation in the design, implementation and monitoring of programme

- Partnership focussed, not siloed, uncoordinated actions à early engagement with dedicated resources for multiple years

- esilient food systems to reduce future humanitarian needs à identify priority actions that can support communities today while building the enablers of future food security

To achieve this, the following has to happen at a meta-level:

This leads to three possible collaboration areas for more resilient foods systems:

- Mindset shifts: Global leadership for concomitant humanitarian-development action, advocacy and championing tangible actions for resilient food systems in fragile settings.

- Tools development and technical support: Evidence-based action is key for larger interventions.

- Capacity building: All stakeholders must receive context-specific training.

Youth

Youth plays a crucial role in food systems. Yet, overall, young people in rural areas do not perceive agriculture and food professions as lucrative or prestigious. Additionally, many young women and men have limited access and control over natural resources, finance, technology, education, infrastructure, and markets. These challenges drive rural youth to migrate to cities or abroad in search of better opportunities. This trend contributes to the emerging phenomenon of over-urbanisation and the increase in unemployment in urban areas, while threatening global food security, as agricultural workforce decreases in regions where it is most needed.

Interventions to address these challenges should involve: (1) ensuring equitable access to resources, (2) investing in training and education in agriculture, technology, finance, and health (3) strengthening the social security system and enhancing the attractiveness of work in the agri-food sector, (4) improving youth representation in political discussions, and (5) supporting community approaches and youth-led organisations. To be effective, these interventions need to be targeted from a food system perspective and follow a multisectoral and multidimensional approach, from analysis to intervention.

Climate-resilient/responsive food systems

While climate-resilient food systems focus on the long-term robustness and the ability to withstand and recover from climate impacts, climate-resilient food systems prioritise dynamic adaptation and proactive strategies to manage ongoing and future climate variability. The presence of one does not exclude the other.

Climate-resilient food systems are designed to withstand and adapt to the impacts of climate change, ensuring food security and sustainable agricultural practices. These systems integrate various strategies to cope with the increasing frequency and intensity of climate-related stresses such as droughts, floods, heatwaves, and pests. Here are some of the key features:

Climate-responsive food systems are designed to dynamically adapt to the ongoing changes and uncertainties brought about by climate change. These systems integrate proactive strategies and innovative practices to ensure the sustainability, productivity, and resilience of food production in varying climatic conditions. Here are some of the key features:

Community engagement, knowledge sharing and local decision-making are essential for the success for both climate-resilient and climate-responsive food systems. Local knowledge, combined with scientific research, can lead to innovative solutions tailored to specific contexts. Collaborative efforts among farmers, researchers, policymakers, extension services and other stakeholders ensure that adaptive strategies are practical and effective.

Index

K-HUB > SDC's Institutional Orientation > Principle SDC food system lenses