True costs of food production in Kenya and Vietnam

Food prices are going up, but the numbers alone do not tell the whole story of how much food truly costs. Even as prices soar, no one pays true food costs when social and environmental externalities are accounted for. This article presents the results of a true cost accounting exercise in Kenya and Vietnam undertaken by the CGIAR Nature-Positive Solutions Initiative. Social externalities were relatively more important in Kenya and environmental ones in Vietnam.

AFS Newsletter - Member Article by

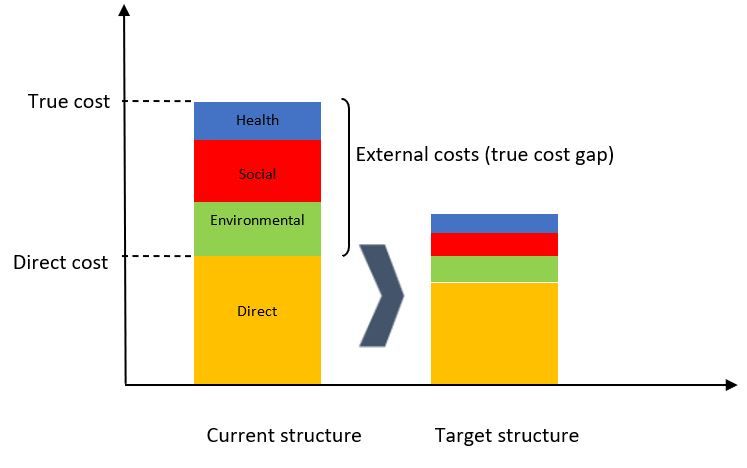

Many countries aim for sustainable food systems, which provide nutritious food equitably without compromising economic, social and environmental objectives. However, most food systems generate substantial unaccounted impacts in the environmental, social and health spheres. These impacts are not reflected in the market prices of goods or services. True cost accounting (TCA) is a method that adds up both direct and external costs to find the «true cost» of food production (Figure 1). TCA systematically measures and values external costs to facilitate sustainable choices by decisionmakers.

Figure 1. The True Cost of Food

The CGIAR Nature-Positive Solutions Initiative (NATURE+) used TCA to understand true costs of food production in Kenya and Vietnam. The researchers analysed national level data on impacts of crop and non-crop sectors, and household and individual farm worker data from NATURE+ sites in both countries.

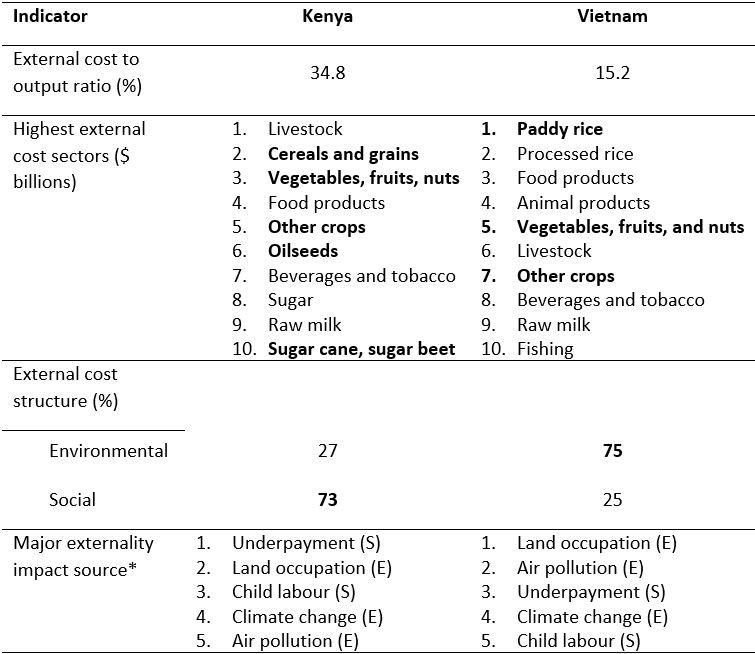

With these two sets of data, researchers estimated costs of social and environmental externalities (human health costs were excluded due to difficulties and high costs of data collection). Table 1 shows findings for the entire agrifood sector at national level for both countries. It shows that for Kenya, considering the entire food system including crops, livestock, fishing, and value addition sectors at the national level, external costs represent 35% of the total value of output. Social costs account for 73% of the total external costs, while environmental costs are 27%. In contrast, in Vietnam, where total external costs represent 15% of the value of output, the environmental costs (75%) dominate social costs.

Table 1. Key findings at national level for the entire agrifood system

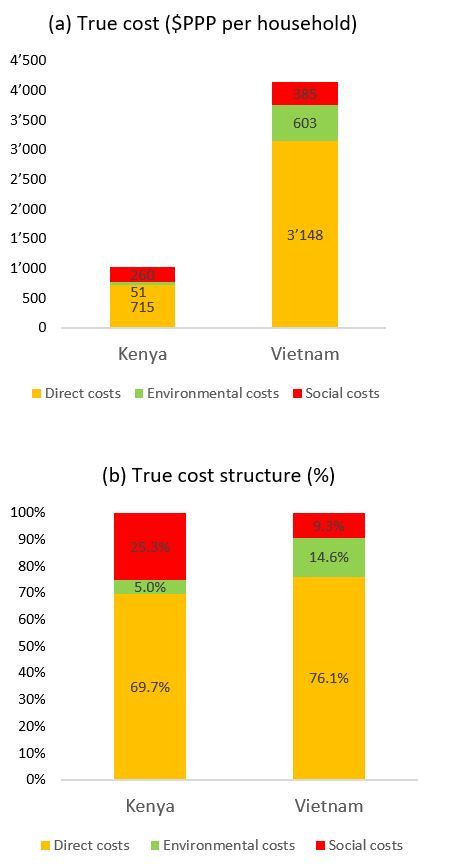

Moving to the NATURE+ sites, we look only at the crop sector (disaggregated livestock cost data in the household survey were not adequate for the TCA analysis). In Kenya, the calculated true cost of crop production is $1,026 per household, which is the sum of the direct production cost ($715 per household) and the external costs estimated at $311 per household. The latter is also called the true cost gap, which in this case represents 30% of the true cost. The breakdown of externalities indicates that social costs (25% of true cost, and 84% of the external costs) dominate those related to environmental impacts, which are only 5% of the true costs or 16% of the external costs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. True costs of crop production for Kenya and Vietnam

In Vietnam, the true cost of crop production is estimated at $4,136 per household, which is the sum of the direct production cost ($3,148 per household) and the external costs estimated at $988 per household, which represents about 24% of the true cost. This percentage relatively lower than in Kenya. The breakdown of externalities indicates that environmental costs (15% of true cost, and 61% of the external costs) dominate those related to social impacts that are only 9% of the true costs or 39% of the external costs (Figure 2).

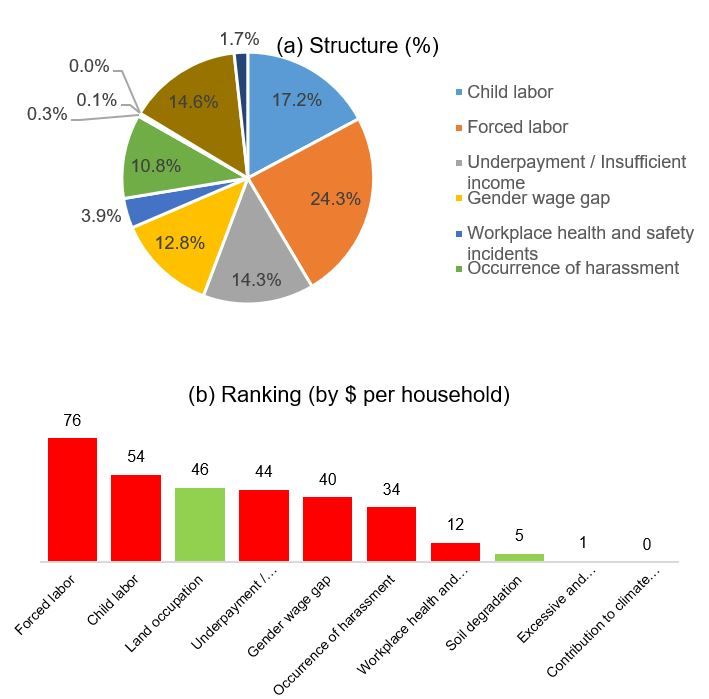

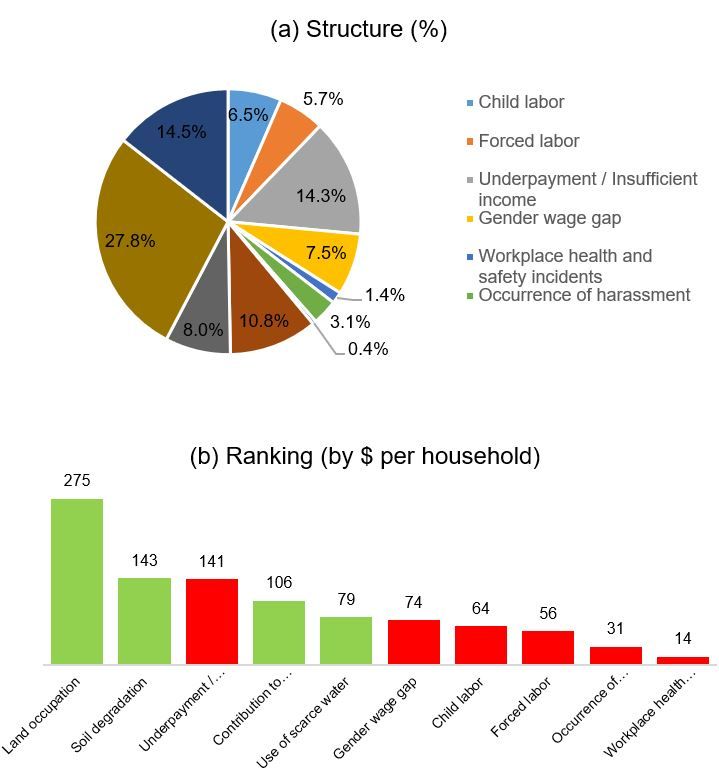

Figure 3 shows the (a) structure and (b) ranking of external impacts in Kenya. Crop production systems in Kenya exhibit relatively high labour-related costs compared to non-labour inputs, with relatively lower intensity in the use of inorganic fertilizer and other chemical inputs, and lower crop yields. This production system leads to relatively greater social externalities. Forced labour is the main social (and overall) external impact driven by factors ranging from «less severe» financial coercion to «more severe» forms of physical coercion. Land occupation is the most important environmental impact, resulting from occupation of lands for cultivation rather than conservation, while underpayment (low wages) and low profits are important social costs that are closely associated with the prevailing gender wage gap and occurrence of harassment. Soil degradation is the only other environmental impact, linked with the use of inorganic fertilizers (60% of households) and pesticides (36%).

Figure 3. Structure and ranking of external costs, Kenya

Figure 4 shows the (a) structure and (b) ranking of external impacts in Vietnam. Crop yields in Vietnam are significantly higher than those in Kenya, likely due to the extensive use of inorganic fertilizers representing the largest direct cost component and leading to a relatively higher level of environmental externalities. In Vietnam, land occupation is the most important external impact, followed by soil degradation and contributions to climate change, primarily due to widespread use of inorganic fertilizers (98% of households) and pesticides (93%). Underpayment and insufficient income are significant social costs, followed by the gender wage gap and child labour.

Figure 4. Structure and ranking of external costs, Vietnam

While both Kenya and Vietnam reveal the presence of environmental and social external impacts in their crop production systems, environmental issues are relatively more severe in Vietnam and social issues relatively more important for Kenya.

As external costs represent a significant part of the final cost, policy and investments that minimize those costs are essential to build an environmentally sustainable and socially equitable food system. Strategies to minimise them could include regulatory adjustments for economic actors; investments in resource-efficient infrastructure and technologies and prudent management of environmentally impactful production inputs and factors. Applying these would mean navigating the limitations and quality aspects of scarce resources like land and water and addressing labour-related issues such as low remuneration, harassment, child labour, forced labour, working conditions and gender discrimination.

Related resources: