Working with the food system concept

How to apply the food systems concept at a practical level?

K-HUB > Dig Deeper: Concepts > Working with the food system concept

Note: A practical how-to tool is being developed for designing projects and programmes that are food systems sensitive.

Introduction

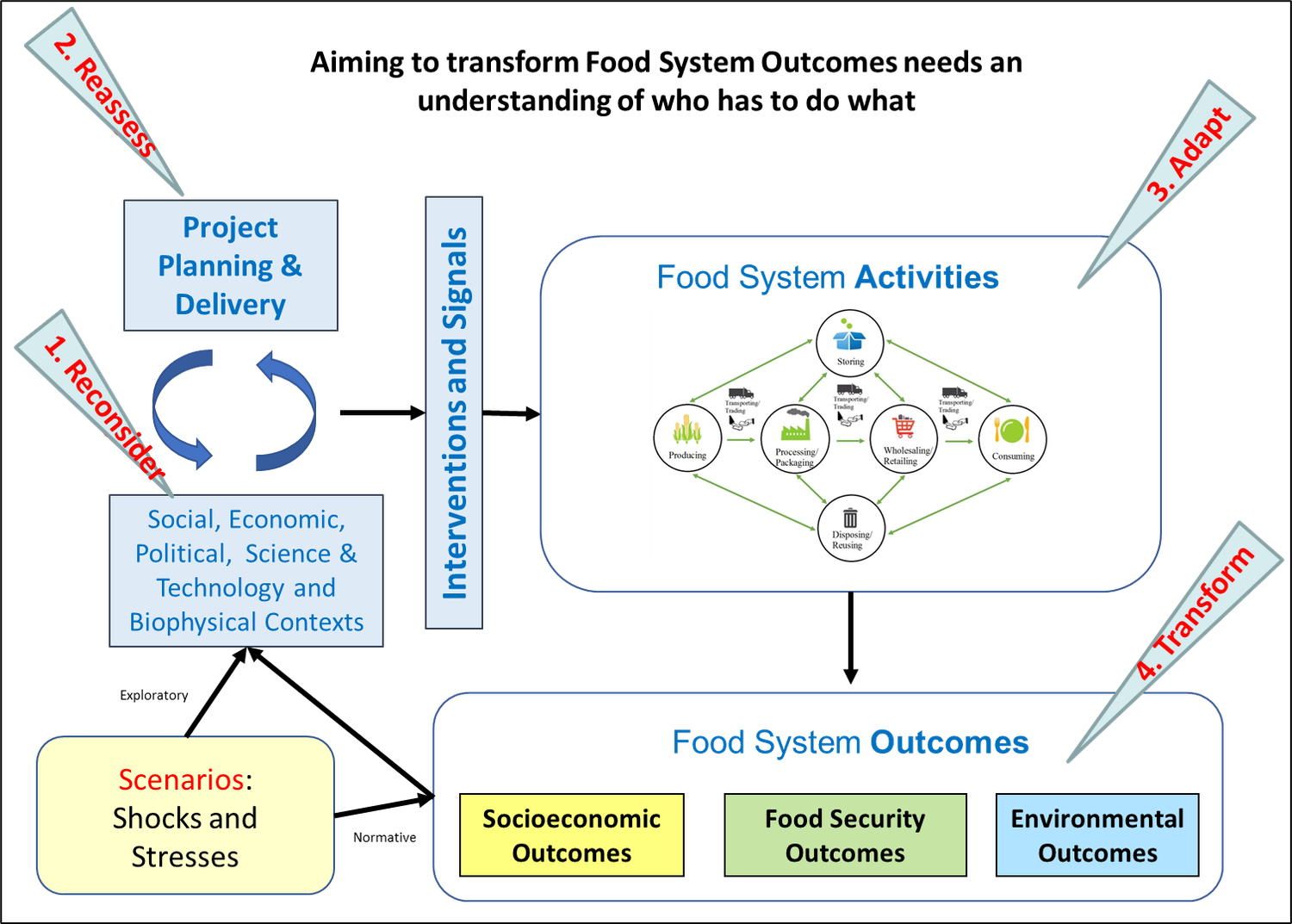

A food systems model (the ‘conceptual frame’), like the one depicted here, serves as a foundation for comprehending and investigating the essential relationships, trends, and trade-offs that form the basis of any desired transformation in how the system operates. By using indicators for the three outcomes (food security and healthy nutrition; sustainable environmental stewardship; economic and social well-being), it becomes possible to evaluate whether food systems are aligning with or deviating from broader societal and environmental objectives. The drivers aid in understanding the forces impacting food systems and shaping their evolution, with these drivers themselves being influenced by the outcomes.

The food system consists of a range of activities performed by various actors, including primary production, processing, retailing, and consumption. It operates within a network of interacting value chains and relies on supporting services like infrastructure, transport, finance, information, and technology. The behaviour of actors is influenced by institutional factors such as policies, regulations, consumer preferences, and social norms, which create the rules governing the food system. Additionally, the food system is influenced by external drivers, including population, wealth, technology, markets, environment, and politics. The outcomes of the food system impact economic and social well-being, food security, and environmental sustainability. It is important to recognise that actors within the food system have different interests, influence, power, and perspectives.

In the context of classic systems thinking, a system comprises interconnected components that convert inputs into outputs or outcomes. The system is bounded, setting it apart from the surrounding environment. Feedback loops within the internal components (sub-systems) and between the system and its broader environment play a fundamental role in shaping the behaviour and evolution of the system. Food systems encompass the intricate interactions between human and natural systems, rendering them complex adaptive systems. Consequently, food systems exhibit significant complexity, uncertainty, and adaptability, often evolving in unpredictable ways that cannot be entirely anticipated or controlled through human efforts.

The value of food system framing

A ‹food systems› framing encourages systems thinking, which involves understanding the relationships and dynamics between different components of the system. It recognises that changes in one part of the system can have ripple effects on other components. This approach helps identify unintended consequences and potential leverage points for intervention to promote more sustainable, resilient, and equitable food systems.

Systems thinking and systems approaches have a long history in multiple disciplines including organisational management, ecology, and engineering. Systems thinking is useful because it helps in building the bridges across traditional disciplinary and sectoral boundaries and accounts for multiple perspectives on situations and problems when developing interventions. It provides frameworks and tools for considering longer temporal scales, systemic impacts, the outcomes of actions, and the learning for all necessary stakeholders. Because of these features, systems thinking and systems approaches are useful when addressing ‹wicked› and ‹super wicked› problems[1] where direct causal links and ultimate solutions cannot be reached.

Applying systems thinking to food system issues provides a more comprehensive and systemic approach to the multiple embedded and interlinked systems within it. It also helps to identify and work with the multiple stakeholders across the food system, and to plan for longer-term and system-wide benefit when it comes to developing solutions that manage trade-offs across environmental, food security, and socio-economic outcomes for increased sustainability.

Systems thinking thereby allows for the consideration of the situation in its totality, its interaction with the wider environment, and its constituent parts and their interactions. all based on incorporating different perspectives.

Balancing food system outcomes: health, environment, livelihoods

Nearly every country in the world faces serious health problems linked to the consumption of either too little nutrient-rich food or too much energy-dense food. Adding the numbers in each of the three categories of malnutrition (i.e. (i) not enough calorie, (ii) not enough nutrients and (iii) too many calories) indicates that about half the global population is affected. The multiple burdens of malnutrition are the new normal, and poor diets constitute the number-one driver of the global burden of disease[2]. Further, current methods of producing, processing, packaging, transporting, retailing, and consuming food are significantly impacting the environment, and the food system is responsible for about one third of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. However, the food sector is the main source of employment worldwide[3], and is especially important in the agro-economies prevalent in most developing countries.

These health, social, economic and environment aspects are outcomes derived from the way people across the food system undertake their activities along the supply and value chain, ranging from primary production to consuming food and managing waste. While some aspects of these outcomes might be desirable, other aspects are not, and hence can undermine equity and other social issues, and degrade the natural resources base upon which our food security depends. Improving food security and other food system outcomes in a fair and balanced way is especially important for poorer and more vulnerable people.

The food system challenge is therefore to achieve food security for all in a growing, wealthier, urbanising world population in a fair and just manner while minimising further environmental degradation and maintaining vibrant food system livelihoods and economies. This is complicated by the background of ‹megatrends› of natural resource depletion, reduced agrobiodiversity, stagnating rural economies, changing climate and a host of social, geopolitical, economic and cultural changes. The ‹food system approach› helps to understand and analyse the reasons (‘drivers’) of the challenge, and to identify the most promising options for enhancing, and better balancing, food system outcomes related to nutrition and health, fair and just livelihoods and economies, and the environment.

Transforming systems

Concern about the way food systems function has promoted recognition of the need to ‹transform the food system›. This is because current food system outcomes are suboptimal regarding health, environment, equity, and animal welfare issues, for example.

While the urgency of food system transformation is now irrefutable, and several priority policy actions to transition food systems towards healthier diets from sustainable food systems have been identified, the phrase «food system transformation» does not clarify what specific elements of the ‹system› actually need to be transformed, as it is very context specific. As a result, clarity is often lacking as to the specific actions that should be taken, by whom, how and when. Food system ‹thinking› can help address this by answering the question of what exactly needs to be transformed.

Although certain sectors of society may have a particular interest in specific activities (and which are normally related to livelihood activities, e.g., farmers in farming, caterers in catering), from a project-level viewpoint, the object should be to transform (i.e., improve) overall food system outcomes, rather than enhancing the efficiency or equitability of individual activities. The objective of food system transformation can therefore be defined as aiming to transform food system outcomes from sub-optimal (state A) to more optimal (state B). Examples include transforming poor diet outcomes to better diet outcomes, poor food safety to better food safety, poor working conditions to fairer conditions, unsustainable to more sustainable environmental outcomes, or poor animal welfare to better animal welfare. The specific goal(s) any project has will depend on its objectives and context, and hence trade-offs between conflicting goals will need to be addressed. However, food system outcomes will not spontaneously transform but only as the result of a food system actor changing behaviour, i.e., adapting an activity from method A to method B. This could mean substantially adapting an activity to lead to a given outcome, or adapting a combination of activities where there is an interaction among them. To meaningfully and sustainably transform a food system, one needs to

- (re)consider the project’s overall context

- (re)assess the project’s planning and delivery so as to propose interventions and signals that will

- encourage the food system actors to adapt their activities to

- deliver the desired balance across all food system outcomes [see figure]

Scenario activities can be used to either explore plausible future contexts the project needs to address (exploratory) or identify pathways to achieve given desired outcomes (normative).

In order to transform the food system outcomes, it is important to develop an appropriate participatory process that brings all the relevant stakeholders together. Figure 4 describes different stages in the process that need to be considered:

Step 1: Stakeholders work to understand the current status of food system outcomes and activities. For this, mapping the existing system with its key activities, outcomes and drivers is the first step that can also be helpful in creating a common understanding among stakeholders of the shape of the current system. Then, using as much available data as possible to create a set of metrics, the status of key food system outcomes that stakeholders are interested in can be assessed. This activity provides the basis for then thinking about which food system outcomes are currently suboptimal and what new mix of outcomes stakeholders would like to strive for (i.e., foresight work to either build a vision on new food system outcomes or exploring plausible futures within which food systems need to evolve).

Step 2: Depending on the purpose of the foresight work, various foresight techniques can be used to ‹plan for the future›. [This figure] describes the development of participatory scenarios, which can help to understand key uncertainties the food system might be facing together with various drivers of change. This analysis allows for the construction of a set of plausible futures/scenarios that can describe various possibilities of how the current status of the food system could change and what this might mean for different actors in the system and for achieving a new mix of food system outcomes. The scenarios can then also be analysed specifically for the differing sets of trade-offs between food system outcomes that the different future configurations of the food system might entail. As any change to the system will be beneficial for some but might bring negative consequences for others, this analysis is particularly important as it allows us to then think about how to deal with/compensate actors losing out in the food system transformation process.

Step 3: This step involves re-examining the current food system map and identifying appropriate innovation pathways for food system activities. Ideally, these need to include coordinated, systemic innovations specific actions for each set of food system activities. The change in activities can be achieved by changing the signals these actors perceive ([i.e., policies, drivers, see Figure]).

Step 4: In the final step of the process a monitoring system needs to be developed that helps to assess if the change in food system activities leads to the envisioned change in food system outcomes. For this the set of outcome metrics developed in Step 1 can be used and adjusted. Monitoring the success of changed practices is crucial for making adjustments in time to not jeopardise earlier successes, or to evaluate the set of transformational activities.

Enabling environments

In the context of food systems, an «enabling environment» refers to the conditions, policies, and factors that support the development of sustainable, equitable, and resilient food systems. This includes creating conducive conditions for production, distribution, consumption, and management of food resources. Enabling environments should be directed at attaining positive food systems outcomes (environmental sustainability, nutrition and food security, economic and social wellbeing), and keep these in equilibrium. Ideally, all food system actors share an interest to create and maintain enabling environments, however the state as a normative body (legislation) and its regulator (coordination, oversight, enforcement) assume an eminent role in ensuring that actors receive conducive behavioural nudges and incentives to act accordingly. Accordingly, as contributors to positive enabling environments, development agencies must work closely with regulators, i.a. bearing the following in mind:

- The regulator has to be aware of the prevailing incentives behind market participants’ behaviour(s) and in a position to independently set rules which guide the incentives and initiative of participants towards good outcomes.

- Markets are not static, they develop over time which means that regulation needs to change as well, without however making markets unpredictable (e.g., through frequent and abrupt regulatory changes).

- Market participants and stakeholders are adaptive. They adhere not only to the standards set by regulators, but also work in an environment of informal rules and practices which need to be recognised and taken into consideration.

- Regulators and development agencies must be aware of these conditioning factors and be prepared to shape these in pursuit of better market functionality. Understanding these market forces, through data collection, monitoring, evaluation & understand of the feedback loops, allows for informed and appropriate regulatory decision-making. In this respect, systems thinking is a step ahead of the classical value-chain approach and offers better entry points to working holistically on markets through systems-based development programming.

In summary, enabling environments are highly dependent on effective regulation which is underpinned by the rule of law, access to land and finance, social inclusion, and skills & innovation. Here are some key aspects of an enabling environment related to food systems:

By fostering an enabling environment for food systems actors such as policymakers, organisations, and communities can work together to address food security, nutrition, sustainability, and equity challenges, ultimately promoting healthier, more resilient food systems for all. In this pursuit, the values and objectives of agroecology have a lot to offer.

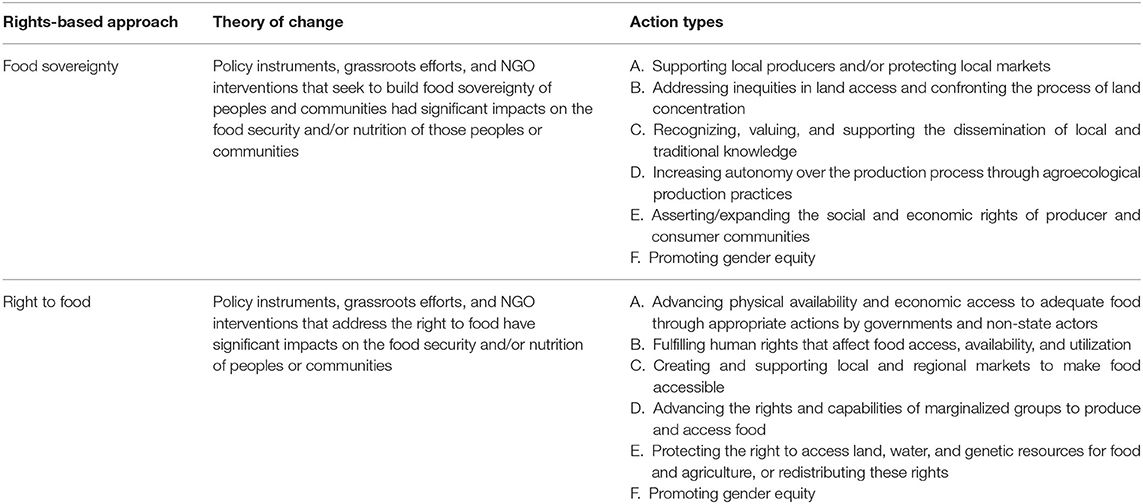

The rights-based approach

SDC engagement with food systems is guided by a human rights-based approach based on international human rights standards and principles (indivisibility, universality, non-discrimination, participation, transparency, accountability and the rule of law). This implies pursuing policy interventions and capacity building projects which ensure that partners (i.a. states, authorities and private sector entities) respect, protect and fulfil their obligations as «duty bearers» and individuals and communities are empowered to claim their rights as «rights holders».

Human rights and social equity can guide the «how» of food system transformation in complement to the «what» should be done (read here about the complementarity and differences of human rights and equity). The cornerstone is the right to food (the right of people to feed themselves with dignity) and many other rights are relevant for a just and equitable food system transformation, for example those relative to gender equality, strengthening of small-scale producers’ agency, rights of Indigenous People and right to access resources (seeds, land or water).

Some examples changes to improve the sustainability and equity of food systems that can be guided by human rights:

- Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions for example through participatory policies in support of agroecological practices;

- Reduction of air and water pollution and alleviation of water scarcity by ensuring access to resources;

- Limit use of pesticides, fertilisers and antibiotics thanks to regulation and taxes on highly toxic pesticides;

- Safeguarding biological diversity and increasing equity by empowering women, investing in youth vocational training programmes, supporting cooperatives;

- Promoting healthy and sustainable diets by prohibiting marketing of unhealthy food or using public procurement;

- Transform food system governance for example by incorporate the right to food and the right to a healthy environment into legislation;

- Enacting legislation on the rights of Indigenous Peoples;

- Banning land, water and resource-grabbing and ensure liability of business for human rights violations.

Example of human-rights based interventions in food systems

The SDC encourages the inclusive participation of all stakeholders in the respect, protection and fulfilment of human rights, both duty bearers and rights holders.

SDC supports right-holders through partners providing awareness-raising to local civil society and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) on human rights, capacity building and training on how to exercise these rights and support for advocacy. Interventions are relevant at international, regional and national levels since many human rights pertinent to food systems have been enshrined in national legislations and are reflected in national jurisdictions, regulations and policies.

For duty bearers (mainly States but also non-State actors such as private companies and international institutions), capacity building enables them to comply with obligations and to attribute special attention to vulnerable or marginalised groups whose rights may be jeopardised by the environmental, socio-economic and health impacts of food systems, including smallholder farmers, in particular women, Indigenous Peoples, racially and ethnically marginalised groups, older persons, people living in protracted armed conflicts and people living in poverty, refugees, migrants, persons with disabilities, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons (LGBT). These groups often have fewer resources, are disproportionately impacted and have less access to basic services (such as health), which increases their risk of illness or death.

Resources:

- SDC practical guide on how to «leave no one behind» in agriculture and food security

- Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food

- Defending peasants’ rights (training and information platform in English, French and Spanish)

- UN Committee on World Food Security: many resources on Voluntary Guidelines on the Right to Food, Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security, reports on «Reducing inequalities for food security and nutrition»

- Civil Society and Indigenous People’s Mechanism at the UN Committee on World Food Security

- Many resources, training tool kits and policy instruments on the right to food

- The Global Network for the Right to Food and Nutrition

- People’s monitoring Toolkit for the Right to Food and Nutrition

- Human Rights 4 Land awareness raising and monitoring tools

- IPES-Food reports

- Geneva Academy reports and policy recommendations on the rights of peasants, right to seeds, right to land, right to food…

- International Land Coalition

References

[1] A ‹wicked› problem is a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognise. A ‹super wicked› problem is where time is running out, there is no central authority, those seeking to solve the problem are also causing it, and policies discount the future irrationally.

[2] Ingram, J. (2020). Nutrition security is more than food security. Nature Food 1, 2. doi.org/10.1038/s43016-019-0002-4

[3] Lang, T, and D Barling. «Food security and food sustainability: reformulating the debate.» The Geographical Journal 178, no. 4 (2012): 313-326.

Index

K-HUB > Dig Deeper: Concepts > Working with the food system concept